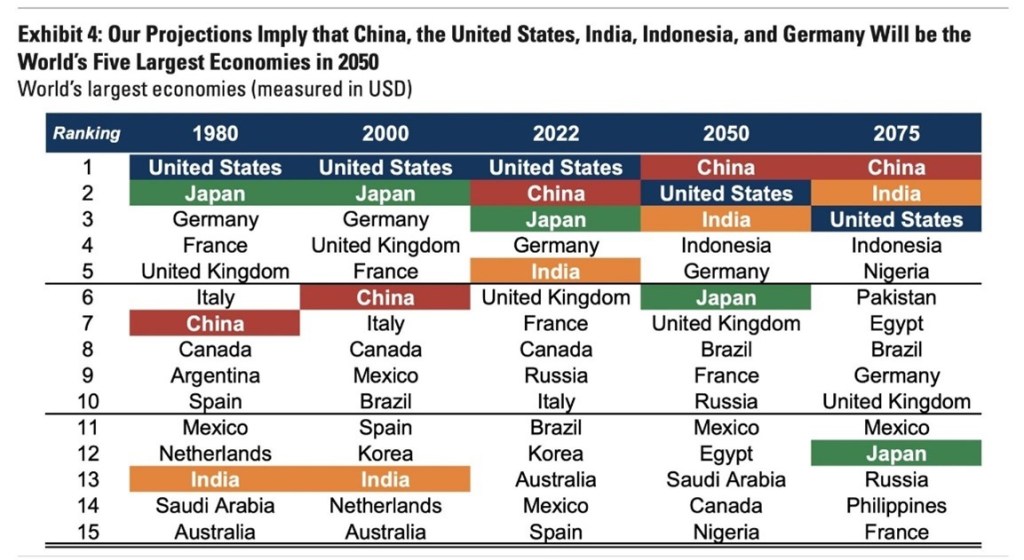

2022 has been a year where geopolitics has come sharply into focus. Nations globally jostle for position in a multipolar world, whether in the US, Europe, or Asia. You hear a lot about US-Sino tensions and for good reason given they’re the two largest economies in the world vying for dominance. Naturally, with China having gone from $1.2tn in output in 2000 through to $17.7tn in 2021 means investing in the region over this time would likely have led to favourable outcomes for investors and certainly come to the attention of American diplomats as a result. Such an omnidirectional investment idea (notwithstanding shorter-term bouts of uncertainty) made me think there must be other regions with equally compelling growth vectors or at least credentials? Given I have the power to look beyond the end of my nose, it’s not all that surprising that India became an obvious candidate, and it seems I’m in safe company as Goldman Sachs project it to be the second-largest economy by 2075:

Figure 1: GS Investment Research

I tend to look back to history to add nuance to the present day but for this post, I’m going to primarily focus on why the country is so compelling for those investors looking to access multi-decade growth opportunities now. Whilst India has very compelling demographics and other social tailwinds, I will focus more on the economics in this post given there’s so much to talk about. I’ll also touch on how the country has developed environmentally and on the benefits of having India exposure within investment portfolios.

The economics

Whilst India’s economic growth has been impressive over the last decade or so, critics will tell you that this growth is all very well but if it can’t invest in its infrastructure, liberalise its trade and financial system or reform labour laws, then India’s ability to sustain its growth will be somewhat challenged. What’s more, with India’s whopping current account deficit, people question its ability to become the next global powerhouse if it cannot incentivise domestic manufacturing enough to establish a robust enough output hub. However, the growth of any nation will always have its inherent challenges and I think a glass-half-empty approach to India is missing the point. Its reviving of the property sector, improving policy, increasing public & private spending and developing start-up ecosystem (amongst others) give it good reason to be looked at in more detail. So come on then, let’s hear the good news.

Let’s start with public finances. I’ve mentioned India’s hefty current account deficit but once you consider the overall trade balance from services, the deficit somewhat nets off, making for a slightly different picture. Indeed, the current account deficit is too adequately financed by improving foreign direct investment inflows and a solid cushion of foreign exchange reserves (India has one of the world’s largest holdings of international reserves). Good. However, that’s not good enough for Modi and the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) as they strive to become more self-sufficient in their goods manufacturing via a comprehensive ‘Make in India’ strategy. Part of this strategy is establishing production-linked incentives (PLI); a form of performance-linked incentive to give companies incentives on incremental sales from products manufactured in domestic units. It is directly targeted at boosting the manufacturing sector and reducing imports in a bid to lure domestic and multinational businesses to centralise their manufacturing base in India (timely, when you consider the impacts zero covid policy is having in China – just look at Apple). It’s clear then that PLI ties in nicely to the growing global demand for manufactured goods such as electronics with India making for a natural home to manage this demand increase given its growing workforce and established know-how in technological engineering.

Next on the hitlist is India’s infrastructure investment (or historical lack thereof). Currently, logistics costs in India are a much higher proportion of overall production costs compared with China, generally making the region less competitive for foreign investment. However, the ongoing build-out of a dedicated freight corridor will see close to 3,000km of rail constructed, connecting the most utilised routes between key cities and cutting journey times in half in a strategy to shift more volume from road to rail, where India currently falls behind other nations. Such developments were echoed last month when India’s finance minister, Nirmala Sitharaman, came out saying that government capex will continue to perform a key role in the region’s economic growth; India’s capital spending budget for the current fiscal year already being 27% higher than the previous year with little signs of slowing.

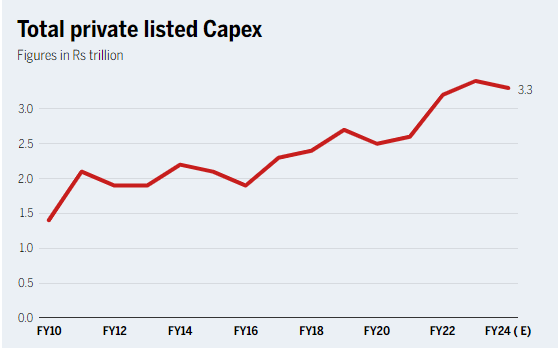

Privately, the story is similar with capex levels incrementally growing. Increased demand visibility, diversifying global supply chains, a developing array of technological products and healthier balance sheets are a few reasons why select industries and sub-regions are paying close attention to bolstering capacity:

Figure 2: Bloomberg, Ace Equity, HSEI Research

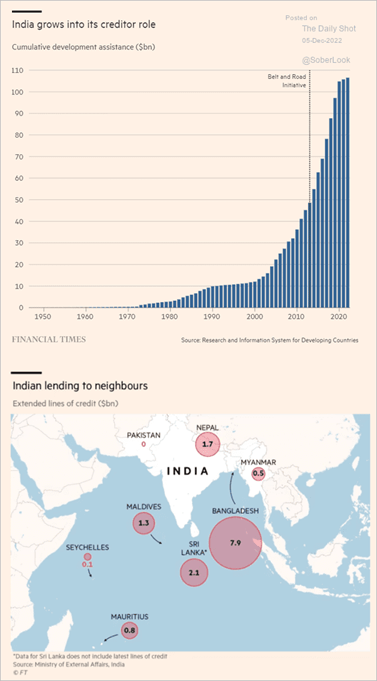

India’s pickup in investment levels can also be seen in its increasing role as an external creditor. Whilst India explicitly plays down its ‘competition’ with China, China’s BRI means that it could become crowded out of investment opportunities in the wider region without active deployment of capital by India’s government. Not without a fight, however, and India’s offshore lending activity makes is clear that they’re not willing to roll over just yet:

Figure 3: FT

FDI and infra is arguably the less exciting part of all this, though, particularly when considering India’s ability to become a technological powerhouse and the growth statistics say it all. In 2018, 20% of the population had access to the internet – that figure is now closer to 50%. In 2000, there were almost no mobile phone subscriptions. In 2020, that number was 84 per 100 people. Put differently, the number of smartphone users in India will reach 732mn this year, more than double the 300mn registered in 2017. Active internet users are expected to rise from 692mn in 2021 to 900mn by 2025. This staggering growth makes clear that India has what it takes to innovate but also indicates towards the gradual compounding effect technology adoption can have in ease of commerce and facilitating heightened consumption. But ‘why has this happened?!’ I hear you scream from the back of the auditorium!! Well, one key driver (amongst many others) of this growth has been the fact that India has one of the lowest data costs in the world. For example, the cost of 1GB of mobile data is 14 times cheaper than in the UK, and 80 times cheaper than in the US.

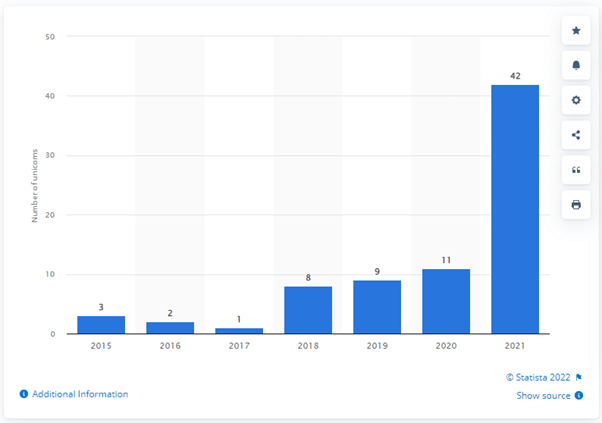

Such innovation is reflected in India’s IP and start-up growth. India’s IP regime includes fee concessions such as a 10% rebate on online filing & 80% fee concession for Start-ups leading to the number of patents filed rising to 66,440 in the financial year 2021-22 vs 42,763 patents filed in 2014-15, according to The Economic Times. Unsurprisingly, this staggering rate of IP growth has also been reflected in the number of unicorns:

Figure 4: Statista, Number of start-ups becoming unicorns in India from 2015 to 2021

What’s more, is that according to Statista, the number of Unicorns by February 2022 was already 92, which again sings to this powerful compounding effect of when innovation turbocharges future innovation.

The signals of positive future growth are therefore not only emerging but pretty well established. However, like I mentioned to a colleague the other week, I could write page after page on why India’s economic growth is not only interesting but impressive but to prevent this from becoming a dissertation, I’m going to move onto how India is fairing environmentally as it rises up the GDP leader board.

The environment

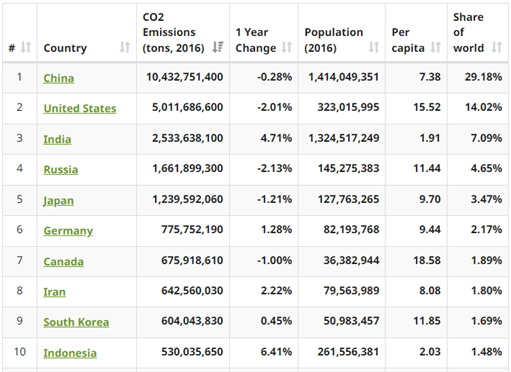

I won’t stay on this point for too long but there’s a small catch – India is currently the globes third heaviest emitting country accounting for 7% of global CO2 emissions (behind China with c30% & the US with c14%) so it would be remiss not to identify that India does face some very severe climate challenges; I list three here to kick us off. Firstly, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has warned that India is set to be one of the countries expected to be worst hit by the impacts of the climate crisis. That was evident in April 2022 where average maximum temperatures for northwest and central India climbed to its highest in 122 years, reaching 35.9 and 37.78C, respectively, according to the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD). Secondly, ten Indian cities feature in the fifteen most polluted places globally. Finally, it’s estimated that around 70% of surface water in India is unfit for consumption. Every day, a staggering 40 million litres of wastewater enters rivers and other water bodies and without the robust infrastructure in place yet, India does not have the means to treat enough of the water to enable it safe to consume again.

Phoar. Ok. So, there’s a lot of work to be done but as I now look to show where the green shoots are in India’s green revolution, it’s perhaps best to first identify that on a per capita basis, India’s emissions look vastly different to that of say the US:

‘That’s not the point, though, it’s all about absolute emissions’ someone heckles from the back of the auditorium (again!). Point well made as whilst per capita is an interesting indicator on things like wealth distribution, standards of living, consumption habits etc, we ultimately need all regions to reduce absolute emissions if we are to keep to a 1.5 degree warming scenario. From deforestation and droughts to air pollution and plastic waste, there are several factors exacerbating climate change and skewing the data in way that puts a positive spin on things isn’t good enough – drastic change is needed.

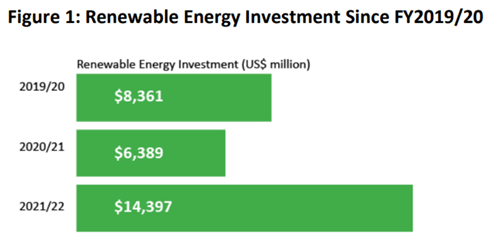

So, what’s the view from policy? Modi is fully aware that with India’s huge scope for growth means its energy demand is likely to grow more than other rapidly growing countries. Modi has therefore put in place more ambitious targets for 2030, including installing 500 gigawatts of renewable energy capacity, reducing the emissions intensity of its economy by 45%, and reducing a billion tonnes of CO2. Global policymakers are pretty good at committing to lofty emission targets they can’t achieve these days so if they are to reach these 2030 goals, then India needs to be someway on the road now. This is where India differentiates itself even more. It has overachieved its commitment made at COP 21- Paris Summit by already meeting 40% of its power capacity from non-fossil fuels- almost nine years ahead of its commitment and the share of solar and wind in India’s energy mix have grown impressively. Linked to the previous section on infrastructure spending, it’s unsurprising to see how much (and indeed the rate of growth!) is being invested in the renewables sector:

Figure 5: JMK Research

This isn’t where it needs to be yet (it needs to be at least double) but the trajectory is establishing itself with clear intent.

As with nearly all net-zero commitments, material issues need remedying, but India’s recent progress is an impressive sign of what we may become accustomed to as FDI increases and infrastructure becomes more resilient.

The role in investment portfolios

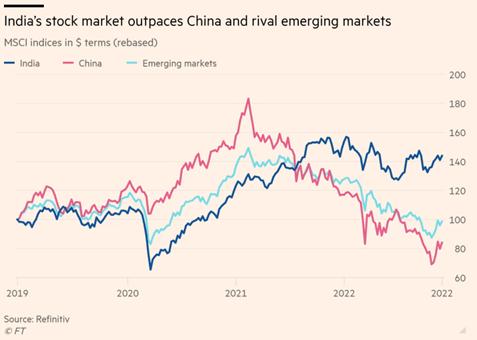

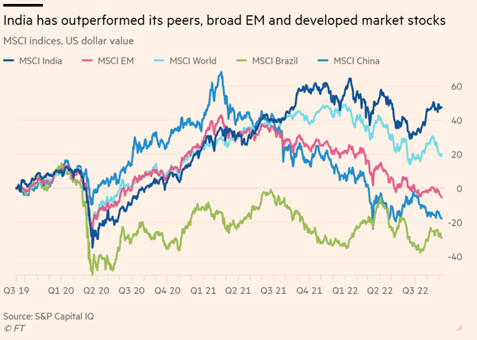

I hope in some way that by this point, it’s clear that India is certainly a region that warrants our attention. Hopefully not from the sidelines, as India has true benefits for investment portfolios, whether as a return engine or diversifier. Firstly, India possesses access to particularly resilient and differentiated return streams vs other EMs, as can be seen below:

Figure 6: FT

Historically, Emerging Market indices have been at the whim of China given it’s been such a large part of the investable universe. However, India is now showing signs of not only forging its own path on the back of robust fundamentals but also in profiting from supply chain disruption in China (as mentioned previously) and taking share in the form of EPS and stock price growth. These impressive growth characteristics aren’t without valuation concern however and according to Soc Gen, India is now trading on a 12-month forward price-earnings multiple of 21 times, ranking as the second most highly valued equity market worldwide behind New Zealand. However, whilst this will likely lead to more disciplined position sizing in investment portfolios, Soc Gen also forecast India’s stock market to deliver earnings per share growth of 19.6% this year so there certainly is grounds for investors to pay up for future growth (albeit not too much!).

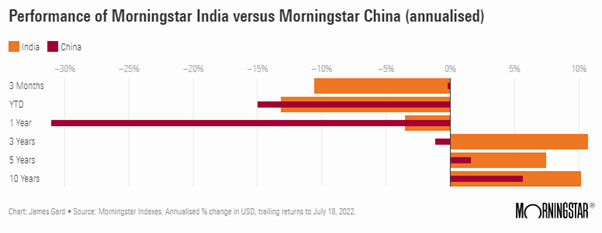

So whilst it’s quite an expensive market, you can see that vs China, India has in many instances provided a positive return skew:

Seeing the above from Morningstar lead me to think about correlation. Again, to use Morningstar indices’, India’s correlation vs the US and global markets is roughly 0.3 and 0.5, respectively. This insulation to global markets will slowly diminish as it becomes a more established global player but in the meantime, investors have the chance to access isolated growth that isn’t dominated by Fed rhetoric or alike, which so many other markets are.

The next question might then be to ask how the market in India is constructed with the presumption that it’s a narrow market and thus the true investable opportunity set is not as great as we might think. There’s an element of that given nearly 50% of the MSCI India index weight is in the top ten but what’s interesting is that the stock market performance in India isn’t necessarily driven by these large-cap stocks. If we compare the MSCI India index to the MSCI India Small Cap performance, the small-cap index has outperformed 50% of the time (since 2009) and in three of those occasions, the outperformance was almost two times indicating that there’s a lot more than meets the eye here.

Conclusion

At a smidge under 2.5k words, this post has been a battle to keep short but that’s a product of just how much there is to discuss when it comes to India’s socio-economic rise over the last few decades. As with any regional growth story, it’s never a linear journey and so whilst we must expect some setbacks in the years to come, the secular growth of the region has many well-founded credentials that investors, economists, anthropologists or just about anyone should pay close attention to if they’re not already.

Leave a comment