One thing I was always taught when faced with a convoluted essay question at university is, whatever you do, do not start with some ‘definition’ you got from the dictionary. Why? Well, they’re pretty vague and only get you so far, and I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t still scarred from some incredibly long and tiresome debates on what does ‘modern’ actually mean? However, I’m going to commit a cardinal sin in this post by starting with one (sorry Prof. Bridger!!):

Centrifuge (noun): a machine with a rapidly rotating container that applies centrifugal force to its contents, typically to separate fluids of different densities.

Excellent. You can all get on with your day now as you’ve learnt something!! Semantics aside, the ‘machine’ in today’s centrifuge is that of our beloved risk-free rate. In other words, assessing the centrifugal impact higher base rates have on the surrounding ‘fluids’; that is, other asset classes. In the age of 40-year bond bull markets post-Volcker economics, equity bull markets since the GFC and beautifully dovish central bank policy across much of that period, we now find ourselves in a time where much of that is reversing. Let’s be clear though, this is not the first bear market driven by rising interest rates and I’m not for one second saying that ‘yeah but now it’s different man; we’ve got NFTs bro’. No no. However, with inflation around 10% in many parts of the developed world and central bank policy increasingly hawkish, I’m going to toy with the idea that we enter a period where neutral rates rest higher than they have been for a while, say 3-4% (partly due to more stubborn inflation than many expect). My question therefore is, how will an age of higher neutral rates impact asset allocators where for so long there hasn’t been these structural implications to grapple with? How do us woke folk deal with it?

Let’s first set the scene. Naturally, the sources of bear markets vary cycle-to-cycle. Demand shock, supply strangle, debt coverage ratios, employment wobbles, house price capitulation etc etc. It can literally be anything. What tends to be consistent is more austere fiscal and monetary conditions in a bid to steady the ship. Aside from the basic impacts higher risk-free rates cause (discounting future cash flows at a higher rate, cost of debts etc), if we work our way out centrifugally from the risk-free rate, you can quickly see how a) their impact increases the costs of capital in places where they need them to be lowest and b) asset class flows will begin to flock back to the ‘machine’ given they’re now paying you more for no real incremental unit of risk. Let’s get some numbers behind this;

- The US 10 Year (UST10 or the risk-free rate) now pays you 4.2% (at 22nd Oct 2022). In December 2021, it paid you roughly 1.5%

- US IG has gone from 2.2% 12m ago to now around 6%

- US HY is now flirting with 10% having been around 4% 12m ago

- Some equity portfolios have implied upside vs fair value above the 100% mark

- EMD spreads have gone from c370bps at the start of the year to now nearing 600bps

- Frontier yields venture beyond the 20% yield mark in some cases.

The list goes on and it all makes sense and seems intuitive but how does this impact portfolio construction and the assessment of risk & return? I’m glad you asked, and let’s answer this through the lens of a multi-asset investor. If we go back to the year I was born, 1995, the juicy UST paid you 7.5% – a yield many institutions looked for. Thus, a multi-asset portfolio could be entirely in bonds to achieve this. Moving forward 10 years to 2005, the portfolio would have to be 50% bonds, 40% equities and 10% alternatives to reach the same 7.5% yield. Moving to 2016, you needed 15% bonds, 60% equities and 25% alternatives. Today, you could get that juicy 7.5% by being 85% in bonds and 15% in equities, and according to Rob Kapito, many BlackRock clients have been structurally underweight fixed income potentially making for a material change in asset class flows. Clearly then, higher rates dramatically change portfolio construction and thus the inherent risk needed to be taken to reach given return objectives.

Moreover, these higher yields, particularly in some of the more esoteric parts of the market, to me, tell you a few things:

- The required return needed given incremental risk shoots up – why would I invest in something inherently riskier when I can park my cash in UST’s, IG, blue-chip equities etc?

- Assuming no material impact to fundamentals, you now get better paid for the same security. All you need to do is by-the-dip (BTD) and stay the course

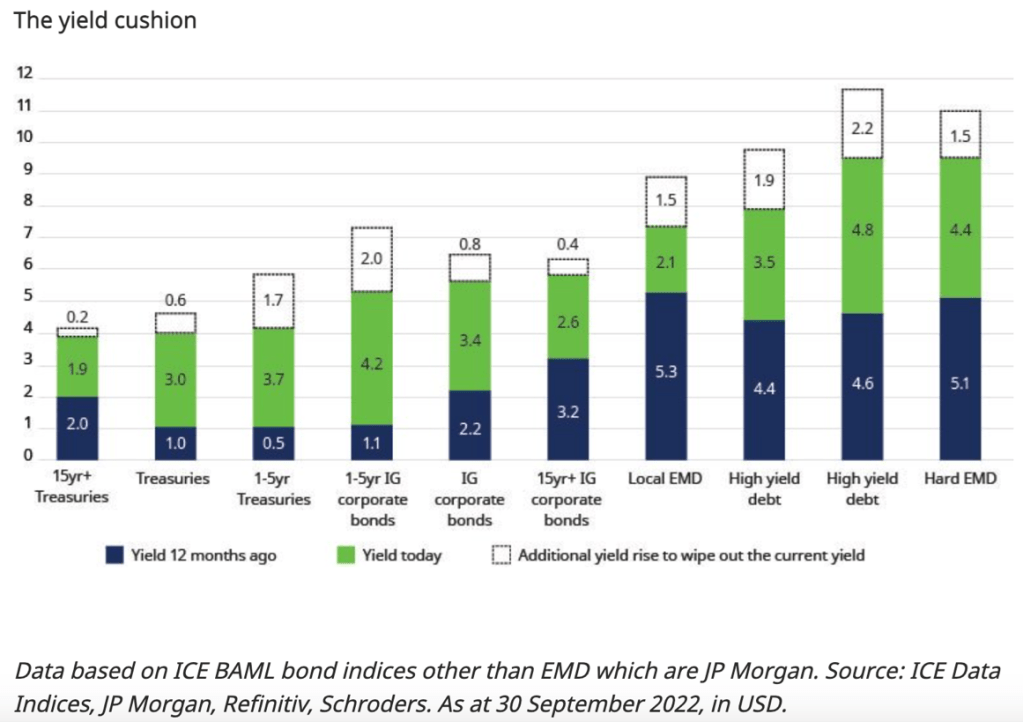

- That you now have a yield cushion to safeguard you against future shocks.

It is this yield cushion point I find interesting as you need to be a medium-term investor to withstand any near-term volatility because as we head into recession, credit spreads could widen further – a dynamic we should be comfortable with. However, you can now lock in attractive yields with a relatively generous margin of safety which Schroders nicely illustrate across a range of fixed-income asset classes:

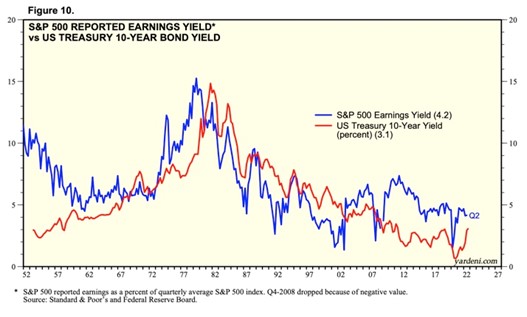

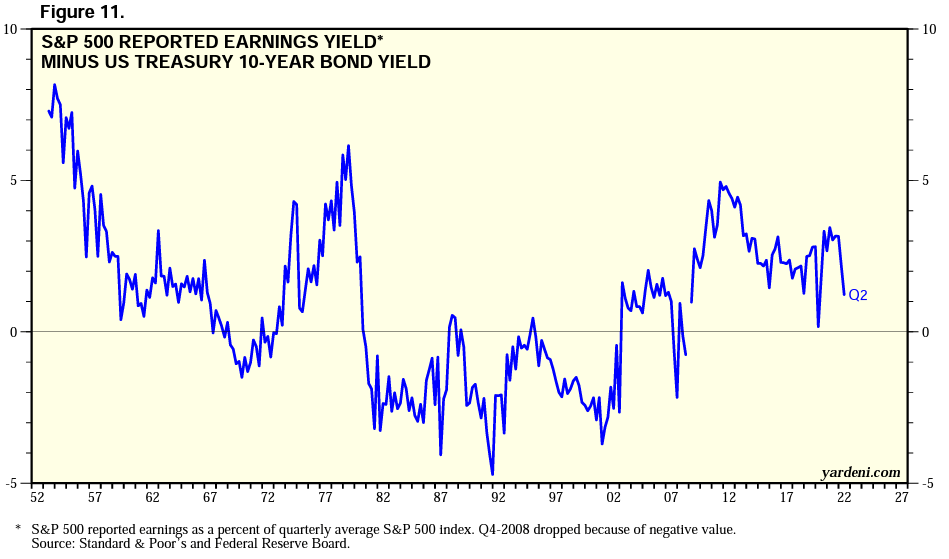

Flipping to equities, the story carries across. Higher rates correlate to higher earnings yields making for more modestly priced securities that should now base underlying earnings more centrally to security price action. You’re likely to see a shorter-term squeeze in the earnings yield (all else equal) given economic weakness, but over a 3–5-year view, you can expect a more attractive earnings yield as businesses modestly re-rate and earnings begin to come through (again assuming a higher neutral rate) at a faster rate than share price growth.

That said, it’s still no surprise that in an environment with elevated base rates, irrespective of higher equity earnings yields, the relative attractiveness of equity trackers begins to diminish and equity selectivity becomes more important.

These shifting dynamics derived from higher rates have multiple implications, but notably, it washes out ‘hot cash’. When you have extreme central bank dovishness like we did over COVID, it’s no surprise you had the boom in new asset classes like crypto, NFTs & non-profitable tech companies to name a few. Money was just so cheap that it got to the stage where people felt that literally anything would go up in value and that there would always be someone else willing to pay more. Keep your P/E ratios; just let me buy it!! Howard Marks would call this the bull market mentality. However, when money isn’t so cheap anymore, and safe haven assets start to give you a return, this draws cash out of these ‘hot’ investments and back into more ‘traditional’ asset classes/investments. (FYI, I’m not being a negative Nancy on things like crypto, it’s just new and people don’t really know it’s role yet, that’s all). This flow mechanism works its way through all asset classes and dampens multiple growth across the board. Just look at the non-profit tech index. Is it any surprise it loosely inversely correlates to UST yields (yes there are more reasons for its decline too…)? I think not:

This isn’t mind-blowing economics, but it is important when trying to understand when certain asset classes are likely to have their time in the sun. If capital starts flowing towards ‘hot’ assets, then that withdraws capital away from others, so it all ultimately impacts the price action of assets that impact each of us – those in our pensions. The withdrawal of hot money also means assets get priced more on their tangible fundamentals making for more intuitive price movement (i.e. removing the froth). If we look at the equity portion of the capital stack, companies that are now trading with impressive EPS growth, FCF generation, improving ROICs etc will begin to get their just reward. Why? Well crudely speaking, investors now need to make extra sure that if they take equity risk, it’s in companies that can perform through the cycle and not those with more ‘speculative’ growth trajectories, particularly when the operating environment is much tougher. There is of course a place for the VC-type mentality, but broadly speaking what I’ve described is how capital flows through the investable universe.

So, to wrap up, rates could well normalise to <2% in a few years’ time and if so, then we needn’t worry about much of the above. However, what this year has shown to the ‘age of woke’ is that we as an industry must maintain a laser focus on the ‘machine’ and not take our eye off the ball on the ‘to the moon’ meme stocks in the hope that market dynamics have structurally changed just because, to use a topical example, Robinhood supposedly makes for more democratised markets. Markets will continue to evolve and new asset classes will present themselves and that’s a great thing, but it takes time to understand where they fit in the value chain, how they can be adequately regulated, how you appropriately value them and what investors can thus expect from them; fiduciary duty is built on these principles. In the meantime, we should be licking our lips with the yields and valuations we can see across many traditional asset classes and importantly that solid businesses, sectors and regions are trading on extremely cheap valuations. So, if you’re a long-term, active investor, now is not the time to be getting flustered and instead is the time to be doubling down on what could be a truly rewarding next phase of the cycle.

Leave a comment