Soaring populations. Ageing populations. Poor demographics. An abundance of pensioners. Secular declines of the workforce and thus global productivity. Yes, for this article I’ve kicked things off with a real ‘glass half full’ mindset. Sarcasm aside, my concern is well founded. Population growth and the demographics therein is, in my opinion, the most underrepresented topic of discussion across public and private sectors. Our population size and composition are the single most instructive factors to a) how we as a planet remain innovative and b) how we orderly decarbonise and create a stable atmospheric equilibrium. For this paper, however, I’m going to keep it focused on how populations and demographics impact our economic growth and power dynamics because, in my opinion, this will underpin most other secular themes in existence. Above all else, I am going to take a leaf out of Elon’s book when I try to simply emphasise how population control/management is the single most important factor in maintaining human peace & longevity.

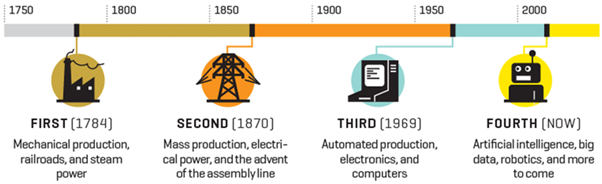

To bet against human ingenuity and adaptability, is, to place the odds of you being correct firmly against you. Humans have displayed an ability to overcome the challenges of life time and time again. The four industrial revolutions are clear examples of technology allowing us to innovate quicker than ever before. The times it took for each revolution to occur become shorter and shorter indicating a compounding effect that in many ways makes for a rather optimistic outlook:

Figure 1: Demandbase, 2017

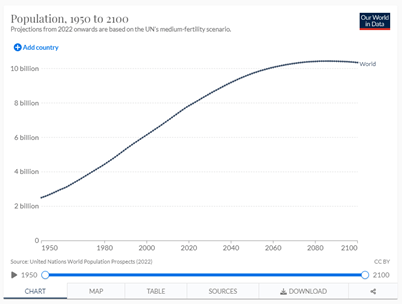

With such an impressive track record of innovating and growing as a species then makes it feel somewhat counterintuitive and historically inaccurate to suggest that our own population growth is the single biggest threat to our sustainable existence on earth. Aggregate population growth is one thing, but demographics within that and the associated fertility rates is quite another. Shifting demographics and changing population growth rates in different parts of the world have, in simple terms, impacts on labour forces, productivity and thus economic growth. With this in mind, let’s put some data behind these big hypotheses. Figure 2 shows the direction of travel for the human population until the end of the century and unsurprisingly we have a long way to go:

Figure 2

Mass population growth isn’t rocket science and is well known by every man and his dog so let’s look under the bonnet. Clearly we’re growing as a species, but where is this growth coming from? Below gives you quite a clear picture if we look at fertility replacement rates:

| Top 10 replacement rates | Bottom 10 replacement rates |

| Niger – 6.8 | South Korea – 0.9 |

| Somalia – 6.0 | Puerto Rico (U.S. territory) – 1.0 |

| Congo (Dem. Rep.) – 5.8 (tie) | Hong Kong (China SAR) – 1.1 (tie) |

| Mali – 5.8 (tie) | Malta – 1.1 (tie) |

| Chad – 5.6 | Singapore – 1.1 (tie) |

| Angola – 5.4 | Macau (China SAR) – 1.2 (tie) |

| Burundi – 5.3 (tie) | Ukraine – 1.2 (tie) |

| Nigeria – 5.3 (tie) | Spain – 1.2 (tie) |

| Gambia – 5.2 | Bosnia and Herzegovina – 1.3 (tie) |

| Burkina Faso – 5.1 | San Marino – 1.3 (tie) |

What I think is clear is the trend between developed and emerging economies and their associated fertility rates. In this example, it’s quite clear how much more fertile, on average, Africa is than say Europe. This is important if we somewhat agree with the endogenous growth theory that a growing working population makes for a more productive and thus powerful economy.

The FT props this argument up (by looking at aggregate replacement rates) but in my view, fails to get to the crux of the matter by not highlighting the true delta in replacement rates across developed and emerging regions:

“In a single generation, societies as different as Iran and Ireland have seen their birth rates plummet in a way that cannot be explained by cultural and religious beliefs. Nor do income levels explain the difference. The United States and countries as diverse as Italy, South Korea, Japan, Hungary, Poland, Russia, China and Brazil are all recording record lows in fertility, and even India is now below replacement level. In fact, over half of projected population growth in the coming 30 years will be in just eight countries.”

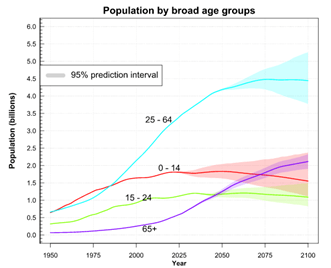

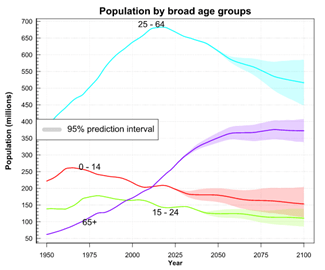

Replacement rates are in aggregate declining but the story is much worse in wealthier economies than in poorer ones – as figure 3 makes clear and figure 4 affirms. Such a trend is occurring where human life expectancy is increasing at a similar rate thanks to improvements in public health and medicine. As such, population compositions become increasingly filled with more pensioners and fewer people of working age. A rapidly ageing population means for a greater reliance on taxes, pension contributions and services provided by fewer and fewer workers. With average life expectancy after retirement approaching 20 years in the developed world and real adjusted returns now firmly negative means higher levels of savings are required to fund pensions. More saving means less consumption, dampening demand for everything other than services for the elderly. Clearly, this is a headwind and thus the working age population and fertility rates act as a leading indicator of how productivity may be impacted in varying parts of the globe.

Less developed:

Figure 3

More developed:

Figure 4

There are many things you can take from the above charts, but the two most notable are 1) how the working population growth rate in less developed regions is set to dramatically surpass that of developed regions and 2) how 65+ populations are set rapidly increase too. The difference is that the rise in the 65+ population in developed regions happens simultaneously to a pronounced decline in the working population. This is where the balance of power between the two may, in my view, begin to change.

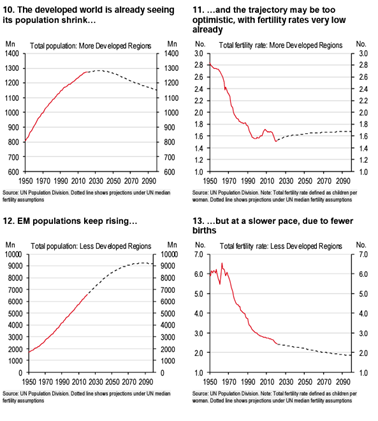

In a research publication from HSBC released recently, they affirm the above point and summarise it well in a series of charts:

Figure 5: https://www.research.hsbc.com/C/1/1/320/cjGpNND

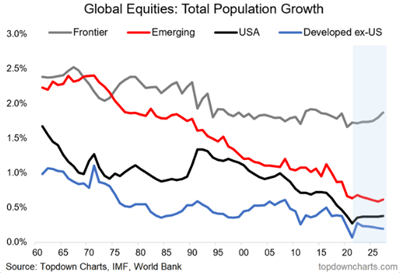

Dissecting this idea further, and as the grid on replacement rates suggested, the epicentre of population growth will likely shift to Africa in the next decades. Indeed, Africa’s population is expected to nearly double between 2022 and 2050. In Asia, in 2023, India will overtake China as the most populous nation. Using a frontier index as a proxy for highly fertile regions such as Africa, you can see this divergence using equity indices:

Figure 6

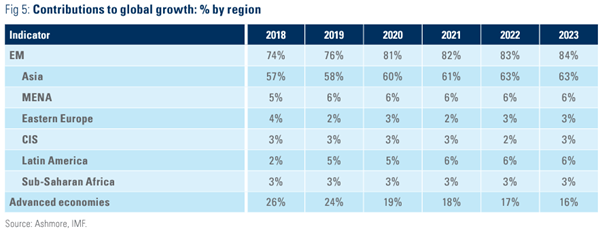

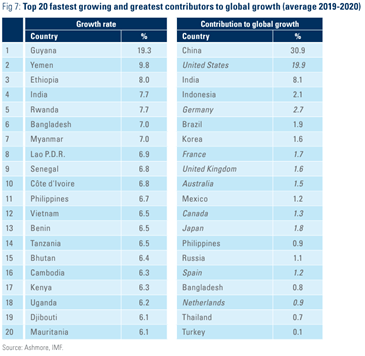

Frontier growth rates have surpassed that of DM for some time and that’s not surprising given where Frontier’s are starting from (see figures 7 & 8). However, this trend coupled with a rapidly expanding workforce will only add impetus to this theme and further entrench the paradigm shift on the world stage. The below two charts make this correlation (or causation?) quite clear and it’s interesting to see Asia’s slow ascent in GDP contribution. What will be interesting to track is whether Africa begins to meaningfully rise too:

Figure 7

Figure 8

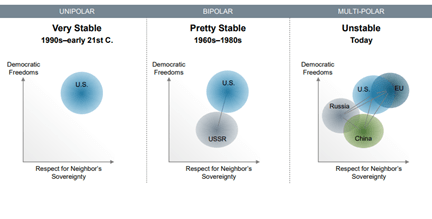

To conclude then, the above data makes for a firm argument that yes, the only constant is change and thus we can expect a continuing shift in the seat of economic power in what is an increasingly multipolar world. Population composition is a very complex matter and I have oversimplified it but for good reason – that being that the overarching impacts will be felt perhaps not in my lifetime, but they will be and by everyone. So what then? Well, using research from Fidelity, you can expect many more bubbles in the multi-polar world and thus a consistently more unstable political environment over the next century:

Figure 9: Fidelity Investments (AART), as of 6/30/22.

It’s vital therefore to develop a nuanced understanding of how globalisation really works and to ensure we remain as integrated with one another as possible to ensure there is either a) an amicable distribution of economic dominance or b) to ensure there do not become independent powers fostering polarised ideologies that nurture xenophobic tendencies. These are big questions that won’t be solved in this blog but are something not to ignorantly dismiss in the hope that Mark Twain is wrong when he says, ‘history doesn’t repeat itself, but if often rhymes’; developed nations being the repeat in the face of the emerging rhyme.

Leave a comment